Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Interview:

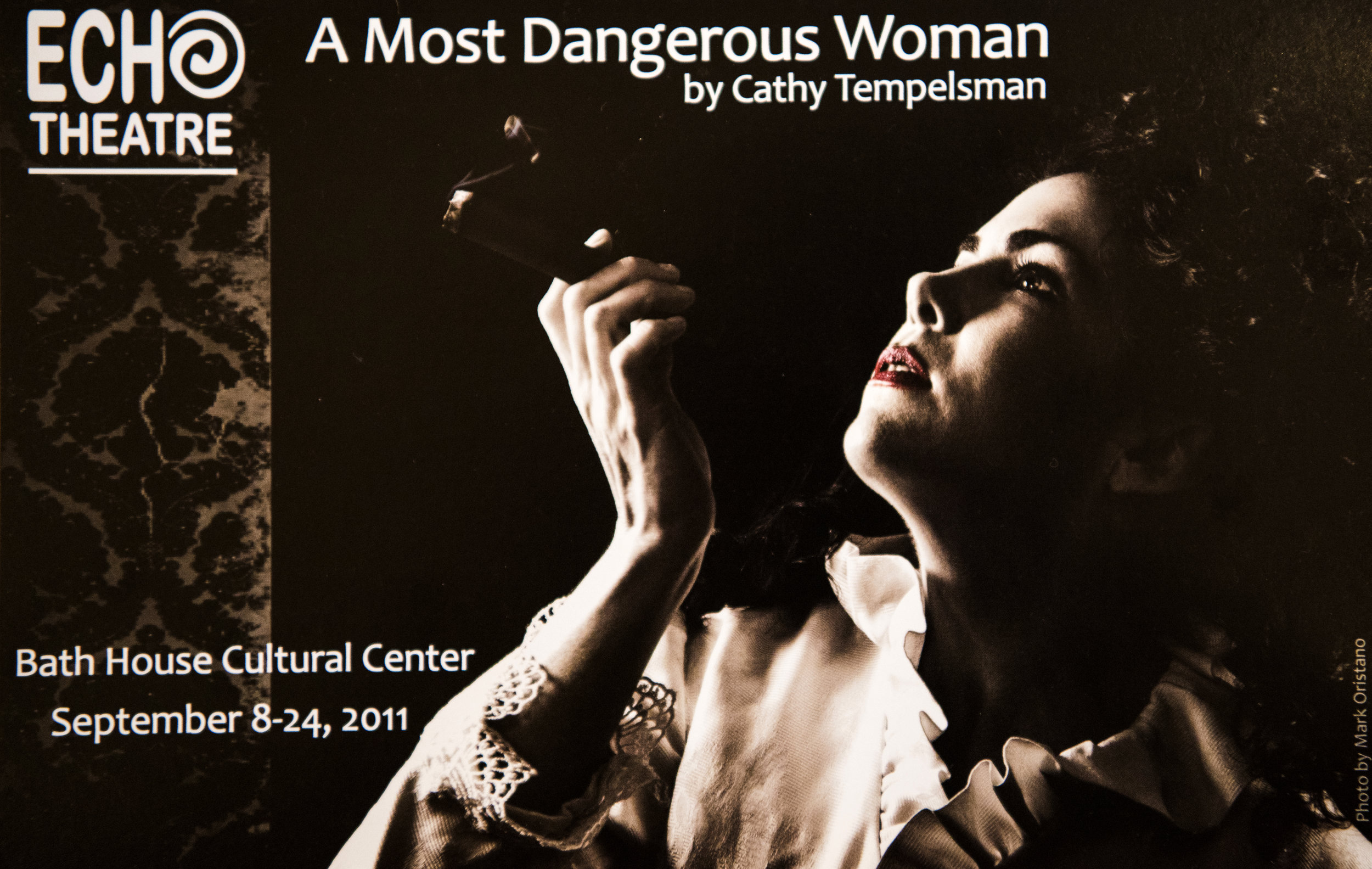

A MOST DANGEROUS WOMAN

Why did you choose George Eliot as a subject for a play?

I fell in love with Eliot’s writing, and then I became interested in her life. She was the most brilliant, fascinating woman I had ever read about—her life was entirely modern and unconventional. Then from the biographies, I moved on to her letters and journals, and all of a sudden a very different George Eliot began to emerge. There was a kind of “disconnect”—as if the biographers hadn’t connected all the dots. Eliot’s letters revealed a much more passionate, complicated person, and an even more remarkable set of choices. They made me understand the novels in a whole new light. And that was the George Eliot I wanted to write a play about.

So is this the first play you’ve written?

It is, but I often joke that it’s also the first four plays I’ve written. Historical plays are tricky, and I came at the material in so many different ways that it was almost like writing four different plays. It took time. Eliot wrote about one of her novels that she started it as a young woman and finished it as an old woman. I sometimes feel that way about A Most Dangerous Woman!

Why did you, as someone who was not previously a playwright, choose to use the form of a play instead of a novel or another artistic format?

I just felt that such a dramatic, controversial life belonged in the theater. Plays tend to provide an emotional truth that biographies don’t necessarily give us. And this was especially important in the case of Eliot. Her life is so full of paradoxes—I wanted to go beyond the facts and the chronology to the person inside. It took such courage to make the choices she made, and I thought, “She must be such an icon for feminists.” But what I discovered was that feminist critics hated her! I thought their expectations were unfair—that they hadn’t looked at her life in context. Writing a play was an opportunity to dramatize the life and the remarkable choices she made, in the context of her time.

What was the traditional feminist take on George Eliot?

Feminist critics wanted to see novels that had female role models, and they objected that Eliot’s heroines weren’t as successful and inspiring as she was—that she didn’t write the life she lived, as they put it. And so they thought she had betrayed women. I thought that was unfair. What many people overlook is that, as a writer, Eliot was committed to realism. She believed art had to be truthful, that anything false in art was “pernicious.” For her, this was a moral issue. It was her manifesto. She was determined to write about ordinary people and real life, and that made her novels truly radical.

People seem to think she approved of the life she portrays in the novels, don’t they?

It's as if she succeeds too well. She portrays Victorian lives so realistically that many modern critics assumed she was endorsing that society. On the contrary, she was exposing the limited lives that women led. I thought it was to her credit that, despite her own success, she writes about ordinary women who wish they could lead meaningful lives. It distressed Eliot that women received what she called a "thimbleful" of education. So I see her as proto-feminist – she had a brilliant mind, and she saw the "Woman Question" in much more complex terms. She thought that men and women suffered because Victorian society had such rigid expectations for both.

What do you think of George Eliot’s essay “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” that condemned a lot of the other female novelists of her time?

Well, she wasn't condemning all women writers. She had great respect for writers such as Jane Austen. She clearly respected that writing. What she was objecting to was what she humorously called "the mind-and-millinery" set – these vapid, melodramatic novels that were being churned out by women. She objected fiercely to the superficiality of this type of writing, the falseness. Again, it was a moral issue for her.

How do you think George Eliot’s unconventional life influenced her novels?

One thing I still find so poignant is that Eliot never set out to be a rebel. She was quite conservative at heart. She desperately wanted the love and approval of her family—and yet she becomes the most scandalous woman in Victorian society. She's almost hard-wired for controversy. And then out of her own experience of rejection she develops a remarkable insight into human suffering and the way people keep the truest part of themselves hidden. Eliot sees beneath the veneer of Victorian society and the face people present to the world—she takes the mirror and turns it inside the human soul. And she does this decades before Freud. She sees that human beings are highly complicated and flawed, that we have unconscious needs and desires. She writes the first deeply psychological novels and changes English literature forever. I don't think people give her enough credit for that. And she truly wants her stories about ordinary men and women to help "enlarge the sympathies," as she puts it. I think all of that comes out of her own experience of being misjudged and misunderstood.

George Eliot famously hated biographies and felt that “The best history of a writer is contained in his writings.” How does that make you feel as someone who is writing a biographical play about her?

She did hate biographies, but there's a little qualifier in one of those letters, where she condones biography of it sets the record straight, or something to that effect. I sighed with relief when I read that—I'd like to think that's the case here.

What about Eliot’s life and A Most Dangerous Woman do you think is most relevant to modern issues?

It's very sad, but in her own life Eliot was forced to go outside her family and conventional society to find love and acceptance. And I think that's so relevant to the debates we still have today about what constitutes marriage and how to define a family. In fact, Eliot's novels are very subversive in this way. Many of her characters are severed from their families—they have to go outside their biological families for love and understanding. They find true affinities in adoptive families and create communities for themselves. In the various readings we've done, audiences have also responded to the issue of female beauty. Eliot was notoriously unattractive—people are always commenting on her appearance—and this has so much to do with the options that weren't open to her as a woman and the scandalous relationship she chooses. I think we still struggle with this. Women are still expected to look and behave in a certain way. Eliot was profoundly sensitive to the difference between a person's exterior and the unacceptable feelings and passions that we're forced to keep hidden.

How did you start writing plays?

I learned about George Eliot and just felt determined to see her on the stage!

How much historical research did you do while working on this script?

I've done a great deal of research. But the interesting thing about history plays is that, ultimately, they have to contain very little history if they're going to work dramatically. Initially, I wrote a one-woman play about Eliot, and it turned out to be a long, encyclopedic, very boring history of her life. I finally learned that an historical figure may have led a fascinating life, but that isn't enough. At a playwriting conference I attended, Romulus Linney told me, "You've been faithful to the book. Now be faithful to the theater." He meant that a play must go deeper than a biography—theater audiences are looking for something more meaningful. The material has to be shaped. With a work of drama, there has to be some invention—you can't simply tell what happened historically, or chronologically. That's why it's thrilling to be doing this play in a theater devoted to Shakespeare. he was the master as far as using history as a starting point

Shakespeare takes an event from history and then changes it to suit his dramatic purposes.

That's right. He locates the human drama ad then shapes the play accordingly.

How many different versions or drafts did you go through? What major changes happened between the first draft and now?

Somebody once told me, "Playwriting is rewriting," and it's true. Plays are written and rewritten, and it's important to love that part of playwriting. Again, I've come at the material in many different ways over the years. It's been a long process and an exciting one. The biggest change is that the script has gone from a one-woman show to a cast of nine playing more than forty different characters. So that's a tremendous change. But it was thrilling to bring these characters to life—along with a Victorian world that's very surprising, even shocking. I think the Victorians sometimes make us look like Puritans!

What was the work-shopping process like?

I've done many different workshop and readings over the years, and it always helps to hear a play before an audience. Richard Maltby became interested in the the script several years ago, and he brought a wonderful clarity and understanding to Eliot's story. It's been a very special, happy collaboration. I think the big difference now is that Eliot is more active in the current script. I realized it was very important for her character to drive the action in every scene, for her to be at the center of every scene.

What is your involvement in the production going to be like?

It's been a joy and a privilege working with Bonnie and Richard. They've brought me into so many aspects of this production, including set design and costumes. It's a new play, and so I'll be doing some rewriting during rehearsals, too. I just feel extremely lucky to be working with so many wonderful, talented people.